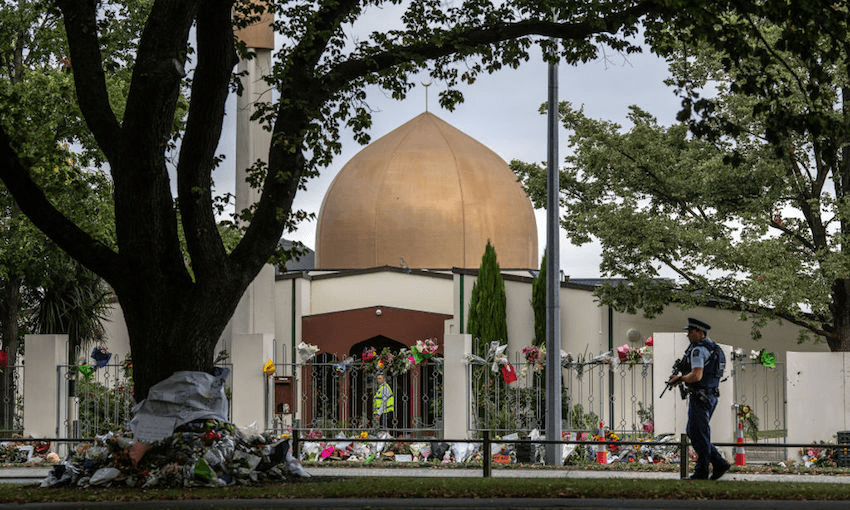

We’ve heard a great deal about the Kiwi response to the Christchurch terror attack but less from inside the event. Historian Ann Beaglehole considers how we support victims to ensure the history is written from their perspectives.

When outside forces attack, there is a risk of victims focusing inwards and becoming alienated. Following the Christchurch mosque attacks, the prime minister’s ‘we are one’, ‘they are us’, and ‘he is not us’ messages and the public expressions of solidarity lessened that risk in the short term. The remaining challenge is addressing racism, ignorance, and the growth of white supremacy and violent extremism in the longer-term.

One way of reducing the risk of victims becoming estranged is by enabling them to tell their own stories.

We’ve already heard a great deal about the government’s response: to restrict the more lethal weapons, try to control internet violence, tighten laws against hate speech and set up a Royal Commission into the attacks.

We’ve been given startling details about the failure of authorities to respond to the warnings of the Muslim Association and others about imminent danger from right-wing extremists.

But we have heard less from inside the event, from the refugees and migrants who had sought safety in New Zealand.

Those stories are primarily theirs to tell. While we may feel solidarity, it is not our tragedy.

As Anjum Rahman, spokesperson for the Islamic Women’s Council of New Zealand, has said, marginalised people face special challenges in being heard due to power disparities. One of the vital roles for those of us who are least affected could be providing a platform for others to tell their stories, perhaps through giving up, or sharing, our own channels. We could offer help to the victims and their supporters to collect the records: texts, and recollections of the leaders and members of the Muslim community, the raw material needed to write or speak from an inside point of view. Such accounts should help ensure that the people most impacted are listened to when or if they participate in the Royal Commission into the mosque attacks, and beyond.

I’m puzzled by the people who have expressed nostalgia for the country’s supposed lost innocence. The view of New Zealand as innocent victim of terrorism is convenient, but unhelpful, as is relief that the shooter was Australian.

Is the implication that we do not need to change, because we are already compassionate, inclusive and tolerant enough? After all the books and reports, how can some people still have false pride in New Zealand as a paradise free of racism and discrimination?

The past unjust treatment of Māori, and of immigrants and refugees, particularly Chinese, Jews and Muslims, are aspects of New Zealand’s distant, and not so distant, record, conveniently forgotten. As refugee rights advocate Guled Mire, from Somalia, has said, too many Kiwis are living in denial about our racial problems and are so quick to shut conversations down. Perhaps the biggest barrier to fighting racism in New Zealand is a reluctance to admit that it exists.

In the years before the shootings, anti-Muslim prejudice – taunts, abuse and occasional violence – was the lot of migrants and refugees who were visibly Muslim. Anti-Islamic sentiment was repeatedly stoked by commentators, including some politicians and officials, many who are scrambling now to deny those past positions and their role in spreading ‘They are not us’ messages. Some people, who are quick to condemn the hatred and discrimination behind the attack, have not taken responsibility for their own part in creating an environment that allowed it to grow.

On the positive side, the Labour-led coalition raised the refugee quota, though selection has continued to focus on refugees in the Asia-Pacific region, and not necessarily on those in greatest need in the Middle East and Africa. Refugees from the Middle East and Africa have had to show existing family links in New Zealand in order to be accepted for settlement.

In December 2018, New Zealand joined 152 United Nation member states in supporting a non-binding compact on migration. The United Nations Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (known as the Global Compact for Migration) aims to bring about more humane treatment of migrants, to ensure the protection of vulnerable children, and help people gain access to basic services, irrespective of whether they had gained formal recognition as refugees.

The Compact angered white supremacists and anti-immigration people around the world, and the Christchurch shooter made clear his strong objections to the compact in his manifesto. New Zealand Red Cross was among organisations worldwide targeted by organised opposition to the Compact when it tweeted that it welcomed the decision to sign the Compact. Immediately the post attracted expressions of anger, mainly on the false grounds that the Compact would take away New Zealand’s sovereignty and ability to govern our own immigration laws. The bulk of the inflammatory posts seemed to be more about sowing discord than expressing genuine concerns.

Yes, there is racism in our country, but also goodwill and plenty to be optimistic about – not least the many people eager to welcome refugees. One of the better news stories since the mosque attacks is about ethnic communities embracing the idea of unity in diversity. One of the themes of a conference, planned by the Shakti Community Council, is: ‘We are different; but we are one.’

We must ask ourselves: What are the stories we want to tell following New Zealand’s darkest day? Who will write the history of the Christchurch terror attack?

Ann Beaglehole is a historian and the author of Refuge New Zealand: A Nation’s Response to Refugees and Asylum Seekers (Otago University Press). She came to New Zealand as a refugee from Hungary in 1957.